This story is part of the New Boom series on millennials in America.

Young people have been the life blood of the environmental movement for decades. There could be trouble on the horizon though, and it all comes down to semantics.

To explain, it's helpful to use the example of Lisa Curtis, a 26-year-old from Oakland, California.

Curtis comes from a long line of environmentally-conscious Americans. Her grandmother, Sis Curtis was an avid hiker and at 84 remains a Sierra Club and World Wildlife Fund member. Lisa's 55-year-old mother, Barb Curtis drives a hybrid car, roofed her house with solar panels, and avoids using plastic except as a last resort.

Although they aren't the types to flaunt it, both women would call themselves environmentalists.

However, it's Lisa Curtis, the youngest of the three, who truly sets the bar for sustainability in this family. She started her high school's recycling club, she traveled to Copenhagen in 2009 to observe international climate talks and she nearly experiences physical pain when she's forced to throw away food scraps in a regular trash can rather than a compost bin.

"It just feels wrong," she says.

But unlike the Curtises before her, Lisa refuses to call herself an environmentalist.

"I think the term has been sort of corrupted... politicized," she says.

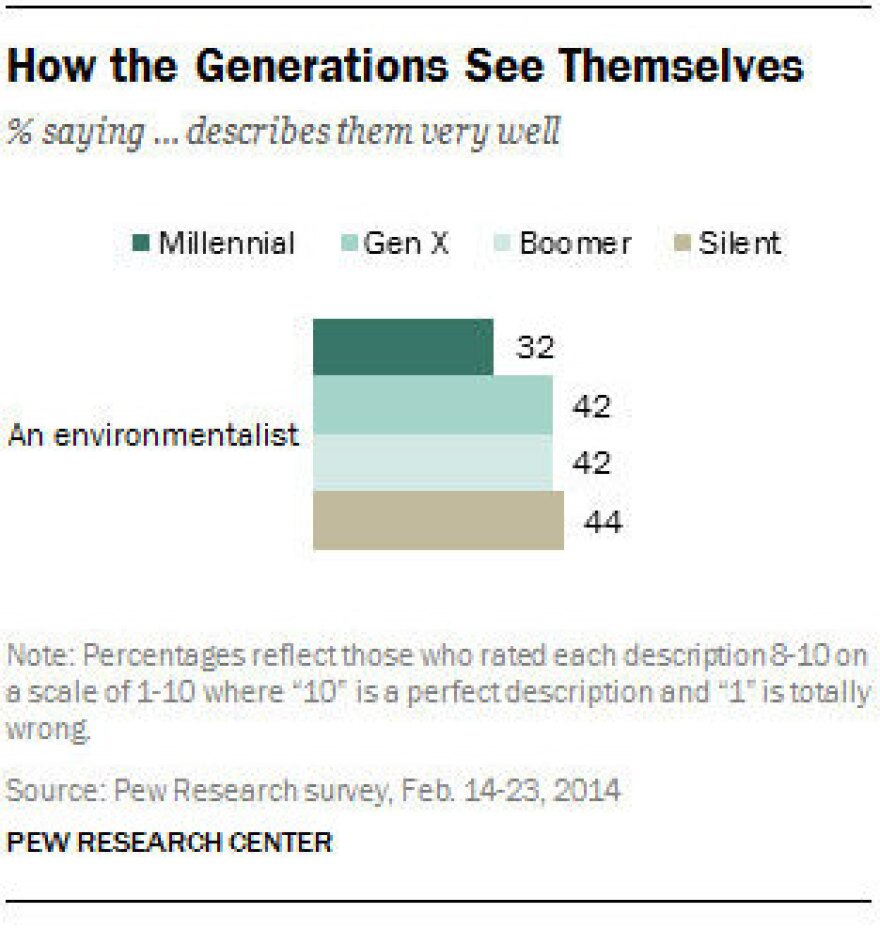

This is the difference when it comes to millennials, 18-33 year-olds. Young Americans, including staunch environmentalists like Lisa, may be turning away from the word "environmentalist." A Pew Research Center poll earlier this year asked participants if they felt the term "environmentalist" describes them very well. Over 40 percent of respondents said yes, except when it came to millennials. Just 32 percent of them agreed. That might not seem substantial, but Pew says it's statistically significant.

The Pew Research Center didn't ask participants for their for reasons why. But Lisa Curtis has a theory: the word "environmentalist" has become outdated.

"It's starting to be used more in a derogatory way," she says. "Oh you're such an environmentalist. You're not in touch with the real world."

She's conjuring imagery that 48-year-old Thomas Hayden, currently a professor of environmental communication at Stanford, is all too familiar with.

"30 years ago — even I cringe a little to remember it — I was sporting white-guy-dreadlocks and living in a commune called the Eco-House," he says.

Today, Hayden's students at Stanford are some of the most motivated, young environmentalists in America. Two of them recently helped convince Stanford to divest all portions of its nearly $19 billion endowment that were attached to the coal industry. This is in line with another point: young Americans are not necessarily any less concerned about the planet's health.

Previous polls have found people under 30 were more likely than older Americans to favor developing alternative energy sources. Millennials are also more likely than other generations to believe that humans are responsible for climate change.

Thomas Hayden wanted to reconcile these two findings. So he recently asked his class, "who identifies as an environmentalist?" In response, only a few hands went up. One student, who'd kept her hand down, explained why.

"'OK, fair enough. I am actually an environmentalist... But I wouldn't say that just anywhere,'" Hayden recalls the student saying. "They understand if they come out saying 'I'm an environmentalist, and here's what I think everybody should do,' that that's immediately polarizing."

Hayden says that's because his students saw how previous generations of environmentalists, including Hayden and his commune buddies, came off as scolding to the general public.

Lisa Curtis wants to stay away from all that. So she calls herself a "social entrepreneur."

She runs Kuli Kuli, a company that helps west African villages economically and environmentally. But the words "environment," "earth," and "climate change" are nowhere to be found in her company's mission statement.

She says that is on purpose.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.