Seventy-five years ago, the U.S. Army began work on a road to connect the far-flung territory of Alaska to the continental United States. This week, the town at the end of that road, Delta Junction, will consider a proposal to celebrate the Alaska Highway’s 75th anniversary. Organizers of a statewide effort to commemorate the anniversary say the highway represents an important historical achievement and a breakthough in race relations.

The Delta Junction City Council on Tuesday will consider a resolution that would launch planning for local events to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Alaska Highway. The measure also calls for the city to accept donations to pay for the events.

Mayor Pete Hallgren says the council also will consider kicking in some money to “... to jump-start that with maybe a thousand dollars out of the city’s funds.”

Fort Greely officials have pledged support for the events, and along with the local chamber of commerce have begun planning them. State Transportation Department spokeswoman Meadow Bailey is heading up a group that’s working on more events to be held statewide. And she says residents of another Alaska Highway community also want to recognize the anniversary.

“Tok is also looking to celebrate the highway and to tie that in with their Fourth of July celebrations,” she said.

Bailey says there’s a lot of interest around the state in commemorating construction of the highway, along with some other mileposts in Alaska history. Those include construction of Allen Army Airfield on Fort Greely in 1942 as part of what was known as the Lend-Lease program that sent aircraft from the United States to the Soviet Union, to help the ally now known as Russia fight the German war machine.

“This year marks a lot of milestones across the state,” she said. “Not just the 75th anniversary of the Alaska Highway, but also of lend-lease, the hundredth anniversary of UAF, the 150th anniversary of the purchase of Alaska from Russia...”

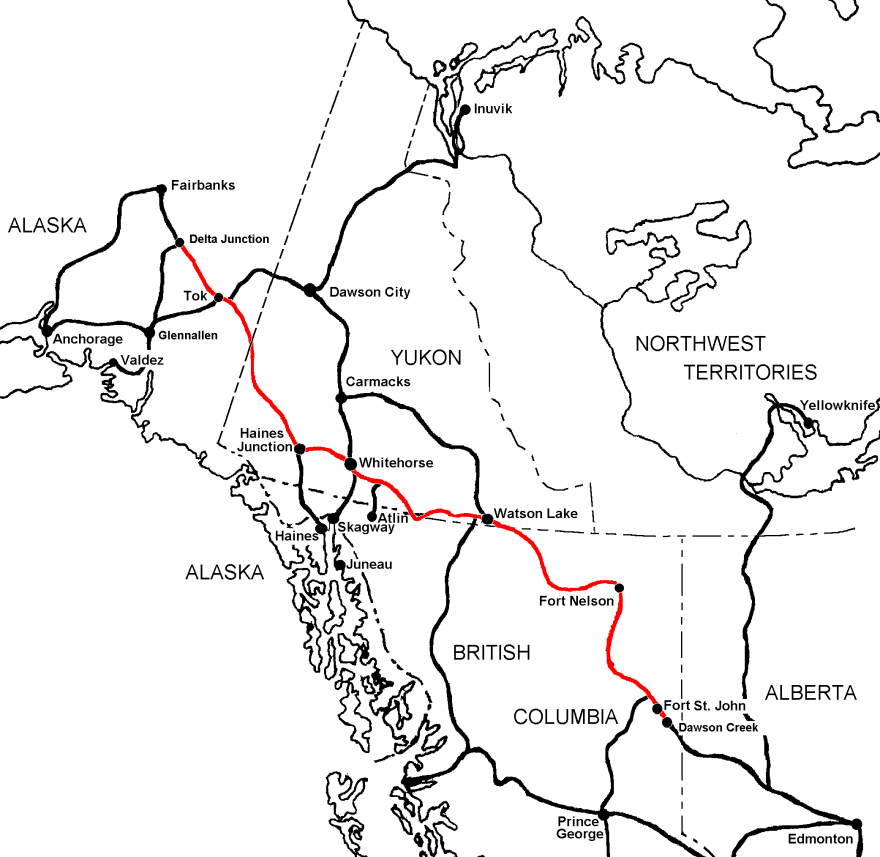

Bailey says her group is coordinating with other organizers in Canada who are planning many commemorative events in communities along the Alaska Highway, which connects Delta to the northern British Columbia city of Dawson Creek. Bailey says the group is looking for new members and ideas for Alaskan observances.

“We’re trying to find all kinds of creative ways to commemorate these marks in history,” she said.

Among the most ardent supporters of Alaska Highway commemorations is author and historian Lael Morgan. She’s researched and written extensively about the highway, and helped organize and support celebrations of its 50th anniversary. Morgan says while researching the history for a National Geographic article, she learned that thousands of African-American soldiers played an important but largely unheralded role in building the highway.

“I discovered a lot more about the blacks who built the Alaska Highway,” she said, “and that they’d been completely written out of history.”

Blacks comprised about a one-third of the 10,000 soldiers assigned to build the highway. They served in three segregated regiments, consistent with U.S. military policy at the time that required black soldiers to serve in segregated units that typically were assigned to menial work, out of a notion they were unfit for more important missions.

“They were consigned to warehousing and stocking shelves and maybe doing longshore jobs,” Morgan said.

But she says a shortage of military manpower in the early going of World War II, and the need to establish an overland route to supply Alaska in the face of Japanese aggression, forced military leaders to send black soldiers to help build the Alaska Highway.

“All of a sudden, the road became very, very important,” she said. “And they had nothing left but black troops.”

Morgan says the black soldiers were assigned mainly to units in Alaska that worked their way south into Canada to meet up with units comprised mainly of white soldiers, who were working their way northward on the road sometimes referred to as the “Alcan,” a conjunction of Alaska and Canada. Morgan says the black soldiers proved themselves every bit the equal of their white counterparts as they endured bitter cold and snow, then torrential rain and mud and swarms of mosquitos. And despite a chronic lack of supplies and equipment, they got the job done.

“What they did with the Alcan was truly amazing,” she said. “They couldn’t have built it without them.”

The black troops met the white soldiers units on Oct. 25, 1942 at Contact Creek, near milepost 590 in the Yukon Territory. A photo of two soldiers, one black and one white, who’d climbed down from their bulldozers to shake hands at Contact Creek captured what Anchorage history buff Jean Pollard says was a breakthough in race relations for the military – and the nation.

“This is a picture where you see a black soldier and a white soldier shaking hands where their bulldozers met,” Pollard said. “That picture went worldwide back then.”

Morgan and other historians say the black soldiers’ work on the highway helped convince U.S. military and civilian leaders to desegregate the armed services in 1948 and contributed to the nation’s broader civil rights movement.

Pollard, a retired educator, says she’s been working with the Anchorage school district to include lessons on the Alaska Highway’s construction in state history courses. And she’s working with Morgan to arrange events in Anchorage to commemorate the 75th anniversary as part of the Alaska Highway Project.

Editor's note: this story was revised to clarify that the executive order that abolished discrimination became official military policy on July 26, 1948.