Anthropologists with the University of Alaska Fairbanks say a site they’re excavating near the Delta River west of Fort Greely was first inhabited by people some 13,000 years ago – not long after humanity crossed over a now-submerged land bridge that connected Asia and North America. The anthropologists say that’s just one of the many discoveries they’ve made at the Delta River Overlook. And they say they’re just beginning to uncover its secrets.

It takes a half-hour Jeep ride to get to where the road peters out several miles into an Army training range west of Fort Greely, where you have to get out and hike. Then another half-hour or so on foot before you reach the site that sits atop a ridge overlooking the Delta River.

That’s where UAF anthropology professor Ben Potter and a dozen workers spent much of last summer excavating material that he says suggests the Delta River Overlook site is among the oldest known human-occupied places in North America.

“Ten different times people came to the site and laid material down,” Potter said in an interview at the site. “The earliest is around 13,000 years ago – so (they were) some of the earliest people to the continent. So, it's very exciting.”

Potter says the site would’ve been the perfect vantage point for ancient hunters to scan the Delta River plain for such big game as bison, which ranged throughout the area during warmer periods between mini-ice ages.

The elevated location also led the Army to bulldoze the spot in 1978, to carve out an observation point for soldiers to use during field-training exercises.

Later that year, the gravelly material exposed by the ensuing erosion caught the eye of Chuck Holmes, a grad student surveying the area under contract with the Army.

“We saw lag deposits – that’s where the sand had blown away, and erosion was down to where the silt occurs,” he said. “And so in this lag deposit there were artifacts and bones and things.”

Holmes is now an affiliate research professor of anthropology at UAF who’s helping the next generation of anthropologists scrape their way to artifacts. But he can’t help but notice the irony in the fact that if the Army hadn’t bladed the area, it may never have been discovered.

“This is what got it all started,” he said as he showed a visitor the site that he’d surveyed nearly 40 years ago. “The Army comes out to do an observation point. Otherwise, who knows if anyone would’ve come back here and looked.”

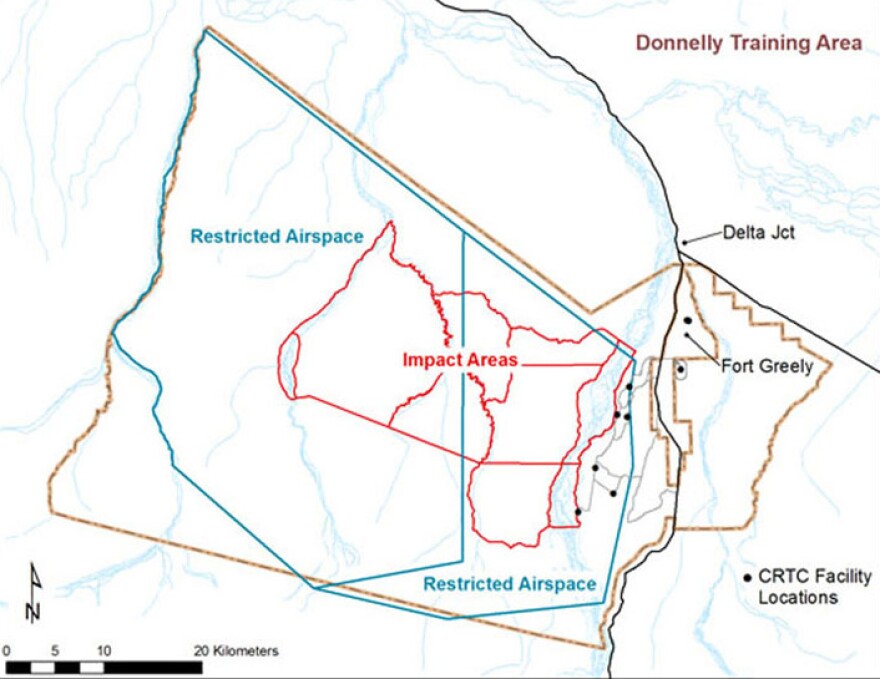

Julie Esdale is an anthropologist with Fort Wainwright’s Environmental Division, and she’s helping Potter’s team coordinate the excavation with the Army. She says there are many more such sites around the 600,000-plus-acre Donnelly Training Area.

“There’s about 450 archeological sites just in the eastern part of Donnelly Training Area that have been identified,” she said.

Potter, the project’s principal investigator, says many of the sites have the same sort of soils and conditions that preserve artifacts for thousands of years.

“That’s kind of unparalleled record,” he said. “There’s nowhere that I’m aware in all of North and South American where you have that density of sites.”

Potter says the artifacts reveal the site was used by the early inhabitants to process the game they harvested. He says he and his team were thrilled last year when they came across the jawbone of a juvenile bison. And he says an analysis of the teeth showed the animal was killed in midwinter, which in turn proves that in some years, humans inhabited the site year-round, even during the cold season.

“As far as my knowledge,” he said, “this is the first winter occupation that we’ve found in Beringia, east or west.”

Beringia is the region that encompasses most of Alaska, eastern Siberia and the land bridge that once connected the two continents and which is now submerged below the Bering Sea. Potter says he and his team have been working in earnest at the site two summers ago. And he says they’re just getting started.

“It looks like a big excavation,” he said, “but it’s maybe 2 percent, 5 percent of the overall area. So we’re just scratching the surface. No pun intended.”

Potter and his crew of mainly UAF anthropology students did appear to be scratching away at the site, using only hand tools – mainly trowels, which they used to extract what seemed like a tablespoonful of soil at a time. Others, like Cassidy Phillips, were screening soil through wire mesh in search of tiny relics.

“Well,” he said, “I’m looking for little flakes like this, or bigger. Any type of tools.”

As Phillips gently shook and scraped the soil around on the screen, a flat fleck of stone a bit bigger than a grain of rice became visible.

“This is a small one, right there.”

The flakes are a byproduct of the cutting tools that early humans were fashioning here. And they’re all over the place, says UAF anthropology post-doc Holly McKinney.

“I have found flakes,” she said, recounting her finds so far that day. “A piece of ochre. Bone.”

The camaraderie, music and occasional outbursts of laughter might make lead a visitor to conclude the site at times seems like the ultimate archeological sandbox. Potter says his crew enjoys the work, but he says they’re serious about the science.

“As we look around with people with shovels and trowels, it’s hard work,” he said. “On the one hand, it’s intellectually very stimulating and exciting. But, we’ve got to move a lot of work to get it done. And we use tiny tools.”

Potter says the tiny artifacts those tools uncover are helping him and his colleagues make big discoveries about the first inhabitants of this part of the world.