UAF archeology professor Ben Potter and an international team of scientists he worked with has discovered evidence of a previously unknown, ancient people who were among the first to cross over from Asia to Alaska more than 15,000 years ago. The scientists based their findings on analysis of DNA from two infants buried more than 11,000 years ago at a site south of Fairbanks. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, sheds new light on when and how the ancestors of today’s indigenous peoples first settled the New World.

Ben Potter couldn’t even get a cup of coffee Wednesday morning, because he was fielding interviews with reporters from around the world who were clamoring to talk about the article that he and two fellow researchers had co-authored – a piece that already had created quite a stir in the scientific community.

“The importance of the paper is, one, that we’ve identified a brand-new population that we hitherto we did not know existed – Ancient Beringians,” Potter said Wednesday. “And, the second is what the implications are for that, for understanding the peopling of the New World. Which, you know, is pretty profound.”

The article is the latest chapter in the evolving study of how humans migrated from Asia to North America – and how some, but not all, went on to settle the rest of the western hemisphere.

“It opens the window for a much wider, more accurate perspective on the complex colonization of the New World,” he said.

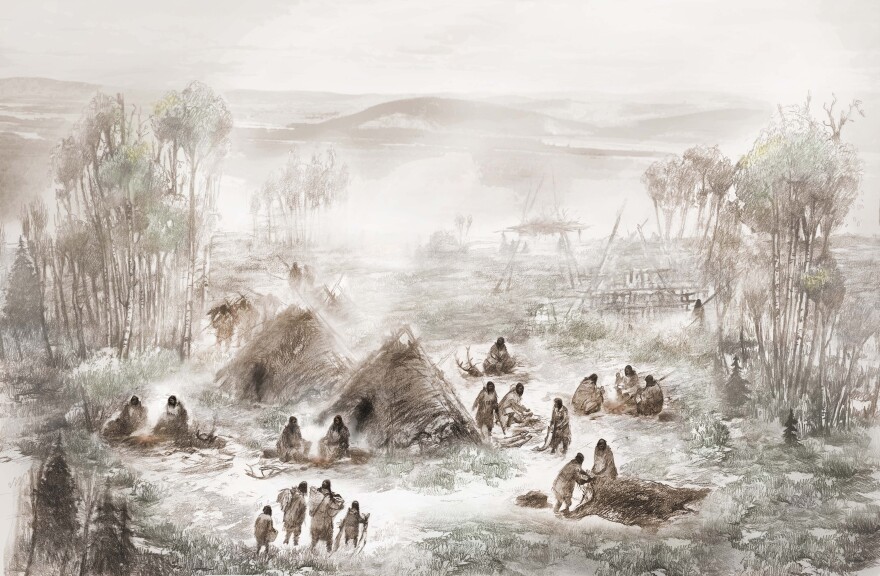

The key evidence that opened that window wide came from DNA samples taken from the remains of an infant girl who’d been buried more than 11,000 years ago at a site located on a ridge above the Tanana River about 50 miles south of Fairbanks. Archeologists first found the remains of a young child at the so-called Upward Sun River site in 2010, and further excavation revealed those of two infants.

“These two were part of an ancient population that came in to the New World, survived, (and) were part of a very well-adapted group of people who survived for thousands of years in the far north,” Potter said. He says the genetic analysis and other evidence confirmed the infant whose genome was analyzed was descended from a group that had separated from other East Asian peoples about 35,000 years ago.

But the data also showed the infant likely was not related to the people who crossed over from Asia and then migrated into both North and South America – the people who became Native Americans. So Potter and fellow researchers concluded the infant was descended from a new and heretofore unknown group they called Ancient Beringians. The name refers to the region known as Beringia, which encompasses most of Alaska, eastern Siberia and the land bridge that once connected the two continents and which is now submerged below the Bering Sea.

Potter says the ancient people settled in Beringia for a few thousand years, despite the harsh ebb and flow of the Pleistocene ice age. “Throughout periods of almost unimaginable climate change, from full glacial conditions to essentially the modern boreal forest, with extinction of mammoth, later on extinction of bison. So, major climate, vegetation and animal abundance changes – but yet, they persisted, throughout this region.”

All of which, Potter says, leads one to wonder: What happened to the Ancient Beringians?

“The answer is – we don’t know at this point.”

But that’s OK, Potter says. He says scientists will continue to search for more DNA samples from early Athabascan peoples, to determine whether they’re related to the Ancient Beringians. And researchers also will begin work on all the other new questions that the study raises.

“Certainly, it provides new questions – which, as a scientist, that’s the most important thing.”

Potter says, however, there’s no question that the history of the New World’s indigenous peoples grows more complex with every new study that’s published.

Editor's note: UAF archeologist Josh Reuther and archeology professor emeritus Joel Irish were among the 18 researchers who contributed to the study published in Nature.